SKELETONS IN THE CLOSET:

LAWSUITS and OTHER EMBARRASSments

Above: "The Sentinel", by Alonzo Victor Lewis, at Centralia Washington.

(Obviously not E. M. Viquesney's "Spirit of the American Doughboy".)

(Obviously not E. M. Viquesney's "Spirit of the American Doughboy".)

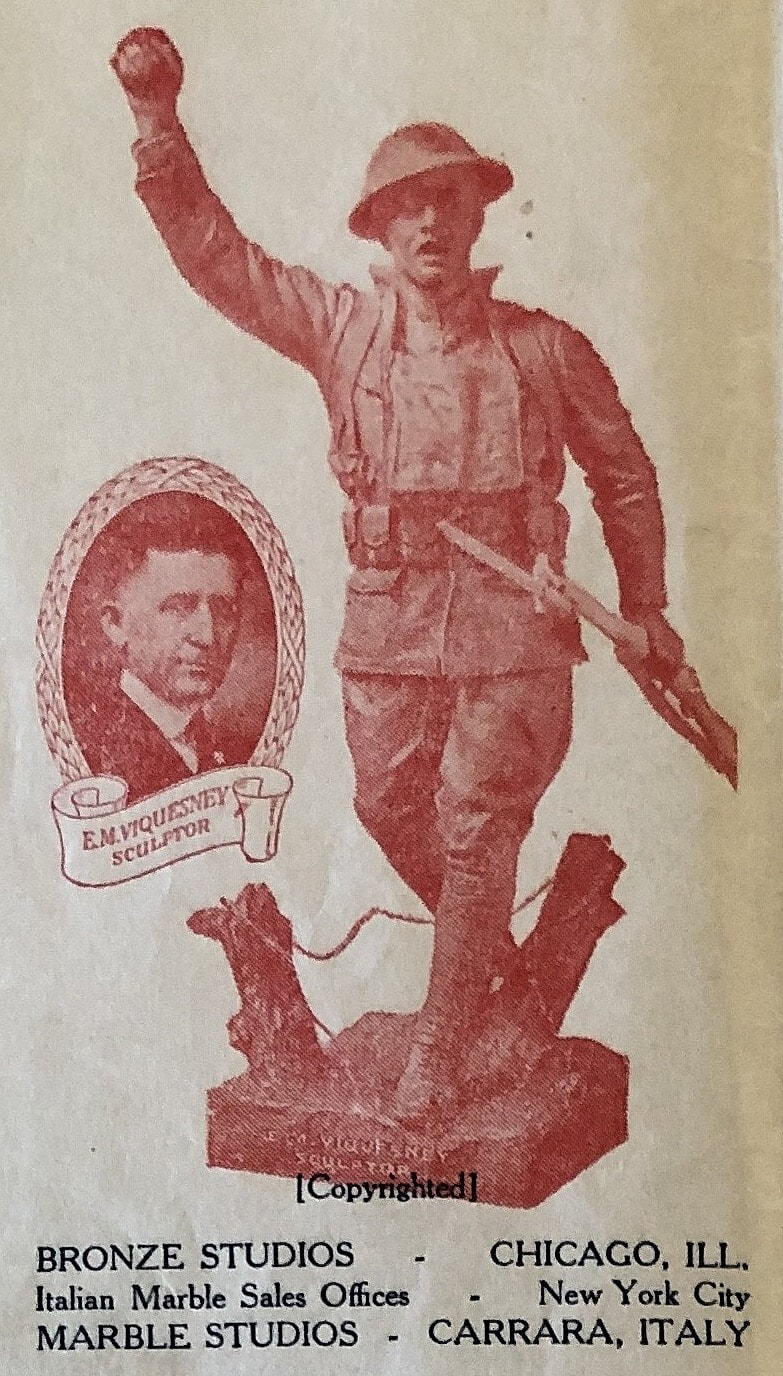

In April of 1921, Viquesney was notified by the American Legion that his "Spirit of the American Doughboy" had won its design award competition for its national WWI memorial being planned for Centralia, Washington. But after complaints were lodged by the "art establishment" that the statue was not a true bronze casting, Viquesney's troubles began. When the American Legion sent a committee to inspect the statue and found it to be made of hollow sheet bronze, the Legion withdrew its award and in 1924 placed a different statue at Centralia, "The Sentinel", by a different sculptor, Alonzo Victor Lewis.

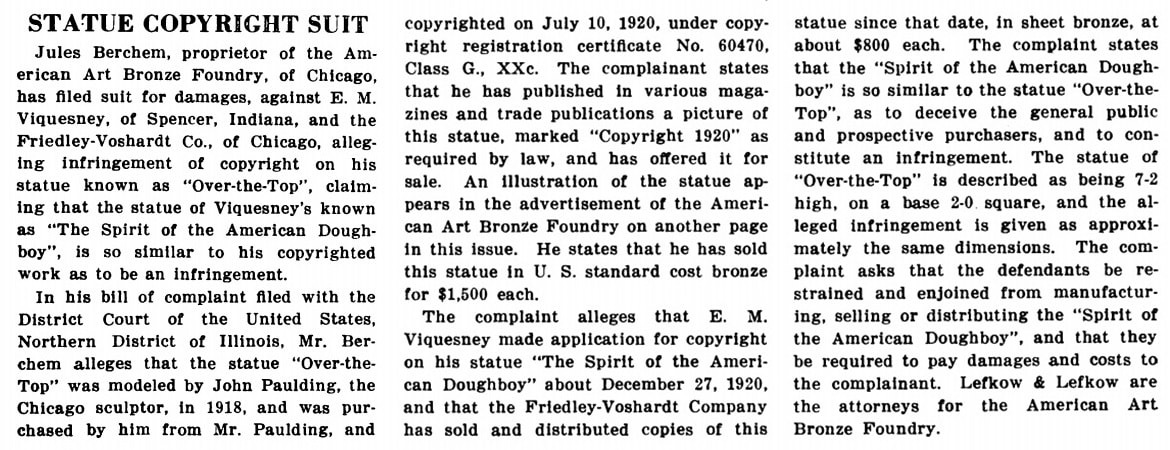

Then, in April of 1922, Jules Berchem, owner of American Art Bronze Foundry of Chicago, Illinois, filed suit against E. M. Viquesney and Friedley-Voshardt Company, claiming copyright infringement upon their client, rival sculptor John Paulding, citing a too-close similarity of Viquesney's statue, "The Spirit of the American Doughboy". to Paulding's Doughboy statue, "Over the Top".

How the suit was settled isn't known, but Viquesney's "Spirit of the American Doughboy" statue continued to be manufactured until the start of WWII. What is known is that earlier in the year (January), Viquesney suddenly and mysteriously sold his entire interest in his Doughboy to his friend and business partner in Americus, Georgia, Walter Rylander, and moved back to his hometown of Spencer, Indiana, perhaps in the knowledge that a lawsuit was about to be filed. Viquesney was able to buy back his Doughboy company from Rylander four years later.

Then, in April of 1922, Jules Berchem, owner of American Art Bronze Foundry of Chicago, Illinois, filed suit against E. M. Viquesney and Friedley-Voshardt Company, claiming copyright infringement upon their client, rival sculptor John Paulding, citing a too-close similarity of Viquesney's statue, "The Spirit of the American Doughboy". to Paulding's Doughboy statue, "Over the Top".

How the suit was settled isn't known, but Viquesney's "Spirit of the American Doughboy" statue continued to be manufactured until the start of WWII. What is known is that earlier in the year (January), Viquesney suddenly and mysteriously sold his entire interest in his Doughboy to his friend and business partner in Americus, Georgia, Walter Rylander, and moved back to his hometown of Spencer, Indiana, perhaps in the knowledge that a lawsuit was about to be filed. Viquesney was able to buy back his Doughboy company from Rylander four years later.

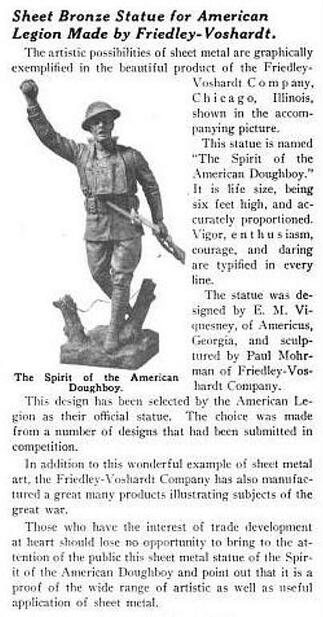

The folks in Spencer, Indiana, hometown of E. M. Viquesney, might start throwing things at me for discovering the trade magazine ad below, left, where it is noted that although the artist indeed designed his famous "Spirit of the American Doughboy" statue, it was actually sculpted by Paul Mohrmann (misspelled "Mohrman" in the ad), who was described by one online source as Friedley-Voshardt company's "talented sculptor". Thus, the sheet bronze version of the honored WWI memorial that stands on Spencer's courthouse lawn and over 120 other places across the country wasn't actually sculpted by the man who billed himself as "one of the nation's best-known sculptors".

|

Above: From The American Artisan & Hardware Record, June 18, 1921. Buried in the text is the startling reference to Paul Mohrman [sic] as the actual sculptor of Viquesney's Doughboy. I can find no later ads or notices mentioning Mr. Mohrmann again.

|

The notice above is typical of Viquesney's difficulty in paying his suppliers. Viquesney produced many electrified items, mostly table lamps made from his popular "Imp-O-Luck" and miniatures of his famous "Spirit of the American Doughboy" statue.

|

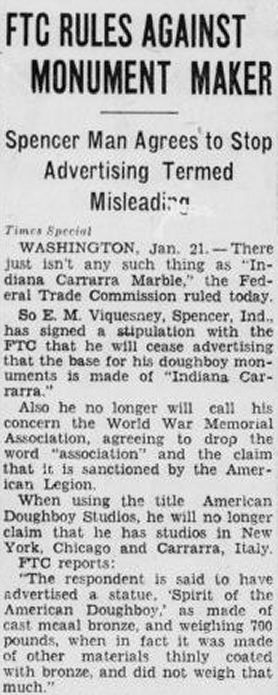

Viquesney's troubles pursued him throughout his career. He always seemed to have difficulty paying his creditors, and in 1936 the Federal Trade Commission filed an injunction against him for misleading advertising in at least five areas.